I wrote this post in two voices: a public one, that tries to apply the wisdom of a beautiful poem to the work I do, and a private one in italics, in which I let the power of the poem help me understand some pain that I have chosen to carry for many decades. I am pretty happy with how it turned out.

I wrote this post in two voices: a public one, that tries to apply the wisdom of a beautiful poem to the work I do, and a private one in italics, in which I let the power of the poem help me understand some pain that I have chosen to carry for many decades. I am pretty happy with how it turned out.

I have been chewing a lot lately on the William Cullen Bryant poem “Thanatopsis”. Published when he was eighteen, it was widely considered too well-wrought to be written “this side of the Atlantic,” let alone by one so young – was considered a forgery, at first, because the transcendence of its insight didn’t seem to match its provenance.

It’s appropriate that the poem’s reception had to do with the mix-up of youth and age, callowness and wisdom. We so infrequently know where the one ends and the other begins; we so infrequently recognize what is most wise and precious when we first see it, because it often seems counterintuitive to what we want to call most valuable. The world has a way of making the last first, of burying the lede, of saving the lesson for after the test.

I think I first read this poem during my tumultuous first year of undergrad. I had been accepted to an exclusive, private undergraduate college, probably part of a national interest in geographically diversifying the elite colleges of the northeast (this was just before any other diversification became an urgent issue). I came directly to college from a competitive public high school in Northern Virginia, but had moved there from Wyoming just two years before, and I still felt quite the hayseed, with shit on my shoes. I remember most of that year living in an existential terror that I would be found out: that I was NOT a well-bred, blue blood east-coaster, and that anyone who thought themselves my friend would certainly think better of it once they really got to know me. In that context I took Western Civ, where I remember being mortified by mispronouncing Goethe’s name in the first day of class, to the amusement of all. I must have read the Bryant poem there, first; it’s mostly a blur of pain and fear, and I ended up transferring west to a state university that felt a better fit for me.

Here’s what I am noting about “Thanatopsis” now: the lesson at the end of the test. The poem is, literally, “a view of death,” and its greatest lesson is that a thing’s qualities, powers, and potentials change depending on how you view it.

First, the poem gives us the view we’ve come to expect of death. It opens with heavy emphasis on describing the inescapability of death and the fear it occasions:

When thoughts of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;—

…And then it makes sure we understand the savage equanimity with which we will all succumb, and be rendered the dust from whence we came:

Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon.

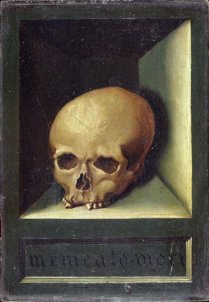

So far, this seems a pretty straightforward memento mori (“a reminder of the vanity of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly good and pursuits”), perhaps befitting Bryant’s Puritan upbringing. To my ear, that’s a poem of despair, ultimately, and the only way to countenance it on its own is through bucking up and bearing the suffering that life deals us. Doesn’t sound like what I want to spend my life doing. But what could our options be?

For Bryant, there are options – and they begin with our point of view. The turn to something more lovely and sustaining comes next:

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre.

Bryant turns the focus away from individual suffering, and spends the rest of the poem exploring the majesty of assuming one’s part in the universal parade of mortality. The poem becomes one of acceptance, even celebration, of the inescapable finitude of human experience – and since none of us can escape the reality that bounds us, it is far better to embrace the ways that our limits enable our potential while we are here. Which ends the poem on something like a peaceful note:

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

The “unfaltering trust” isn’t in God, necessarily – I don’t find God in this poem, not explicitly. Instead, it’s in the rightness of the way things work out, and in the peace that comes from ceasing struggling against the current that’s more powerful than anything else we know.

I have struggled to make sense of my terrible first year at Wesleyan ever since I left it. Why was I so unhappy? Was the problem with the school itself: the snobs, the judgment, the social shibboleths that no one ever taught me? When I was there, I sure felt that was the problem: them, not me. I felt so much pain, and I turned the pain into anger at everything around me. Before I left that year, I sneaked into the house of the fraternity that had refused to accept me because I wasn’t well-bred enough and stole a silver loving cup of their mantel. I still have it; for decades, it has represented my “getting even” with a group of people who caused me a lot of hurt.

But now, I have different perspective: I see it differently. Maybe part of what was getting in the way of my relaxing and accepting the opportunity that had been given me was my own fear, my own conviction that in fact the admissions committee HAD made a mistake; that I DIDN’T belong because I was a hayseed. The social psychologists call this “stereotype threat” – that place where our knowledge of how others MIGHT see us negatively cause us to see those negative attributes in ourselves, whether or not they are actually there, and underperform accordingly. The real truth is probably somewhere in the middle: in the early 1960s, that place WAS a bastion of exclusivity; in the early 1960s, I was supremely sensitive to any hint that I was being excluded.

I do know that my son ended up attending that school twenty-five years later, and visiting him felt like something being made whole. The place has become aggressively inclusive in the interim, seriously dedicated to creating an environment where all are welcome. I had lunch many times in the dining room of the same fraternity that wouldn’t have me a quarter of a century earlier, wondering at how easily my son and all his wildly different friends got along so famously, and how warmly they included me as one friend among many.

Maybe it just wasn’t time for me to be there in 1962, and it was in 1991. Maybe I was spending so much time in struggling against some inevitable force my first time around that I couldn’t see that the outcomes were out of my control: that the simple fact of the social climate of the early 60s was that I wasn’t a fit there, and could be (and was) somewhere else. Or maybe I was writing my own story so powerfully onto the reality of the place that it really didn’t matter what was real: I was going to live the story I brought along with me, no matter what. Either way: maybe the place didn’t change so much as my perspective on it did. Either way, I could have had a different story had I tuned in to the reality outside my story a lot sooner. I am stunned to realize how much pain I might have avoided had I simply changed my point of view earlier.

This is why I am so impressed by this poem, lately. It used to be about the futility of trying to accomplish anything, since the end of all of our efforts is ultimately foretold. Now it is about accepting the actual limits of our world and thriving within them anyway – of finding faith and hope to persist in the very limits that used to keep me from feeling it.

The thing about reality is that it doesn’t change: we do. We have power over the reality we make. We can carry stories that render everyone around us our opponents; that make all differences into battles to be won; that make every challenge to our own story a threat to hammered out of existence using the tools most readily available. Which, sadly, tend to be the habits we learn through our education (as Parker Palmer says, “when we get surprised in an academic context, we reach for the nearest weapon and try to kill the surprise as quickly as we can, because we are scared to death”).

The limits we all have to our intellects, our capacities, and ultimately our time can be raged against, or accepted and worked within. The choice is entirely ours – if we have the will to choose to become the masters of our own perception and commit completely to living life on life’s terms. Acceptance of reality paradoxically opens us to the only way to really change our experience of it, as surely as death ceases to terrify once we accept the way that its limits empower us to live in fuller connection with those with whom we share our finite, beautiful journey.

My son had a poetry professor at that college who refused to teach free verse – only structured forms like sonnets, villanelles, and sestinas. My son told me how he growled on the first day of class, in his Manchester brogue, “I seek to teach you the liberating power of constraint.” Our constraints can liberate us – if and only if we accept them and take a different view of the truth they offer us. When we are fully connected to reality, possibilities appear where before there was only pain.

Image of Parkin’s Memento Mori, borrowed from the Twitter feed of the Ferens Art Gallery, with thanks.